|

History of Meihuazhuang

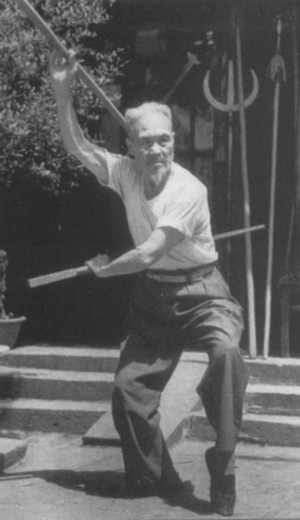

Photo of Meihuazhuang master Han Qichang from Spring 1991 Grandmasters magazine Meihuazhuang is said to belong to the Kunlun school and together with Baguaquan (a style of no relation to the famous Baguazhang popular today) comprise the fundamental boxing styles of the Kunlun sect1. In many of the rural areas in which meihuazhuang has been practiced for centuries, the founding of the sect is attributed to the mythological figure Yun Pan. Villagers often say “Meihuazhuang existed since the beginning” and folk legends claim that its history extends to the Han dynasty. Meihuazhuang's oldest written records, genealogies and textual date to the records of 2nd generation master Zhang Sansheng. While these writings have been accurately dated by historians to 1588, the style itself is undoubtedly much older2. Based on historical records, it is known that in 1588, Zhang Sansheng began his studies of meihuazhuang publicly in Xuzhou, Jiangsu province. His student, Zou Hongyi, of the third generation, was born at the end of the Ming dynasty. By the 9th year of the Qing Dynasty emperor Qianlong's reign, Zou Hongyi went north to teach martial arts and settled in Mazhuangqiao village in Pingxiang county, Hebei. The fourth generation masters Zou Wenjiu and Zou Wenrei taught meihuazhuang boxing to villagers. Records and rhymed couplets found in Mazhuangqiao village, Hebei are evidence that the organization of the meihuazhuang sect into the wenchang (civil/arts & meditational aspect) and wuchang (martial aspect) had already appeared. The fourth generation master Cui Guangrei came to Hebei, settling in Qianwei village, Guangzong county, where he taught meihuaquan. A commemorative monument to master Cui's contribution was erected in 2001. A historical text of meihuazhuang, the Genyuan Jing, notes that Zhang Congfu, a master of the 8th generation, like his predecessors taught martial skills (wugong) to the next generation to “enable them to come to realization or enlightenment” and taught meditation arts and theory (wenli) so that “people could come to understand the laws of nature to dispel hardships and cure diseases”. Zhang Congfu changed the large jiazi exercise patterns (Dajia) to small Jiazi exercise patterns (Xiaojia), a change which allowed the jiazi to more accurately reflect the guiding principles and central spirit of the wenli (civil/arts meditational aspect). In the meihuazhuang homelands on the North China plain, many folk stories exist surrounding the exploits of past masters such as 9th generation master Wu Qingchang in Dongzhao village, Guangzong. Legends state that his extraordinary martial skills enabled him, while standing in a narrow alley, to defend himself from all objects thrown at him from people on the rooftops. It is said that, when this master died, 10 000 people lined the streets of the village all the way to his tomb. Many similar oral histories relating to the exploits of famous masters reveal much about the history and belief systems of the rural people on the North China Plain. Footnotes

Practice Methods and Social CustomsOriginally, meihuazhuang was often practiced on the tops of over 100 stakes or posts driven into the ground, giving rise to its name “Plum Flower Posts”. The height of the stakes varied according to the practitioner's skill level. Training on these stakes develops highly precise footwork and balance. Meihuazhuang was passed only within family clans and was a “secret” style closed to outsiders. Later in its history, teachers relaxed proscriptions against non-family members and opened their teachings to outsiders. However, the acceptance of students into the sect as “inner-door” students was governed by strict rules. Generally new practitioners undertook 3 years of jiazi training before their teacher would begin their formal instruction. During this 3 year period, students were observed carefully to see if they possessed the necessary determination and moral qualities demanded by their teachers. After the basic skills had been acquired, two years of additional training in fighting techniques provided the practitioner with well rounded skills for further study. This process is reflected in the popular meihuazhuang idiom “San nian jiazi, er nian chui” (Three years of jiazi, two years of boxing). Over time, the primary practice methods of meihuazhuang shifted from training on posts to training on the ground. While reasons for this shift can only be speculated upon now, several theories are contemplated1. Since at least the end of the Qing dynasty, the style has been primarily practiced on the ground but maintains the powerful spirit, precise footwork and awareness of balance and “rootedness” as when practiced upon stakes.

Local museum of Boxer Rebellion history focusing on the life of Zhao Sanduo. Wei County, Hebei, 1992 In 1900, long periods of drought, injustices by foreign missionaries, high taxes and rampant corruption in the Qing dynasty government led to the peasant revolt known as the Boxer Rebellion. Because of the organizing structure of the wenchang extending over a broad territory and uniting the entire school, meihuazhuang played an important role in the peasant uprising known as the Boxer Rebellion of 1900. Zhao Sanduo, from Shaliuzhai, Wei County studied meihuazhuang in his youth and later became an accomplished teacher. Witnessing the hardships faced by rural people, he later became a chief organizer of the Yihetuan Boxer Rebellion. In 1895, in the border regions of Hebei and Shandong, he established many locations for the teaching and training of more than two thousand students. In the 1890s in Liyuantun Village, Guang County (Guangxian), Shandong province, the villagers rebelled against the Christian Church and the Qing government, which had forcibly attempted to convert the local Yuhuang (Jade Emperor) temple into a Christian church. In 1896, invited by Liyuantun village, Zhao led his followers to assist the village in their cause. Upon arrival, they held martial arts competition and performances for three days to demonstrate their martial skills. This performance attracted a great deal of interest and martial arts enthusiasts from all the surrounding areas came to attend. The Qing soldiers, intimidated by the display, were afraid to destroy the temple. Later in 1898, Zhao Sanduo organized an uprising which was suppressed. In 1901, he joined an uprising led by Jing Tingbing. In 1902, Zhao Sanduo was betrayed by a traitor and was imprisoned in Nangong County where he died of starvation after refusing to eat.2

The home and headquarters of 1901 Rebellion leader Jing Tingbing. Guangzong County officials Li Yunhao and Zheng Lanhua hope to restore the degraded site. Guangzong County, 1998 The large number of stories illustrates the tremendous popularity and reputation of Jing Tingbing as a folk hero who was executed as an enemy of the Qing dynasty government. In the 1960s, Chinese universities (Shandong University played a major role in the research) undertook large-scale oral history projects which collected a wealth of stories about folk rebellion and martial heros in northern China especially in Shandong and Anhui3. They represent a tremendous source of information for ethnographic and historical research of the region. After the defeat of the Boxer Uprising in 1900, meihuazhuang's connection with the movement was discovered by officials. They persecuted practitioners and branded the school a “heterodox sect” banning the practice of meihuazhuang. The school continued to exist as an underground movement for many generations. To avoid being discovered, disciples of the school practiced indoors or late at night. Suppression campaigns against the boxers, indemnity levies and increased taxes forced increasing numbers of people into banditry. Fighting between republican and loyalist forces during and after the 1911 revolution greatly disrupted society. Though banditry had been common in the region since the late 1800s, by the 1920s warlord fighting, military corruption and taxation caused social and economic decline, widespread famines and exacerbated rural poverty4. The social disruption which followed led to a breakdown of socioeconomic systems to the point where “brigandage assumed truly endemic proportions”5 by the 1920s. Lawlessness prevailed and it was only the martial societies which banded together to form village militias which were capable of providing any protection for the common people6. The long period of banditry ended in the 1930s as political stabilization allowed economic conditions to improve but its effect on society was profound and is reflected in part by the folk beliefs of the area. During this period, meihuazhuang played an important role in self-protection and the protection of villages. During the cultural revolution period, the school was once again branded a “herterodox cult” and banned. It is important to note however that the longstanding historical view of meihuaquan as a heterodox cult regularly engaging in rebellion similar to other religious cults is unfounded. Historians Esherick (1987) and Lu (personal communication, 1998) assert that mainstream meihuaquan was concerned primarily with martial arts and was not a sectarian religion. That the “the main stream of the school was quite independent of (and even antagonistic to) the sectarians” (Esherick 1987 p.52) is supported by local stories about antagonistic martial competitions between meihuaquan adherents and White Lotus sectarians. To this day, the elderly meihuaquan teachers most familiar with oral traditions assert that the sect never had any connection with the White Lotus sectarians. In the 1990s, proscriptions against the practice of meihuazhuang were lifted. The practice of this ancient and historically important art, which can improve the health of local people and benefit the rural society, is now largely unrestricted. The efforts of dedicated rural politicians of Guangzong county and Professor Yan Zijie have contributed greatly to this positive change. Footnotes

Also in this section:

|